If ever he writes a memoir, it will reliably contain the falsehood that in 2019 he quit the United States for Côte d’Ivoire to sit out the coronavirus pandemic. Also, perhaps that he wished to elude a great—and imminent—North American meltdown.

Half-truths rather than outright lies. He relocated to Abidjan, to Babi as the Ivorian commercial capital is nicknamed—Babi la belle, to give it in full—to take up a job with an international organization. Nearing fifty, the decision strikes him as a last-ditch lunge at pursuing a conventional career, a move both disparate with a listless adulthood and yet of a piece with previous flights: an earlier one out of the U.S.; from Kenya; from South Africa; and while still a teenager, out of Britain.

He has left behind, in Washington, D.C., a wife and young son. Left behind too his octogenarian mother and father, who encouraged him to accept the job. His parents have strong attachments to Côte d’Ivoire, where they spent eight years. In fact, he has returned to the country, having spent two years of his adolescence here. And yet one lie he does not permit himself is that he knows the country well.

_____

He arrives at a moment when the coronavirus is just stirring, is little more than a rumored peril. On this evening in December 2019, throngs are gathered outside the airport doors awaiting no one in particular. On the coach ride to his hotel—the streetlights seem set to three-quarters power, giving the night a smeared, lurid cast—he sees on the highway signs names he has nearly forgotten, names familiar from Alpha Blondy songs. Marcory. Adjame. Cocody. The activist musician—still very much alive—has slid almost into oblivion. His prestige had never rebounded from his decision to flatter powerful but authoritarian politicians rather than remain true to the democratic themes of his lyrics.

Eager to move out of the hotel where he lives during his first week, he rents from an old acquaintance a one-bedroom flat in the city’s business district, Plateau. What attracts him to the neglected tower building at the southern tip of Plateau is its commanding views over the city and encircling lagoons. Its location permits him to walk to work.

Residences Belles Rives, designed in the 1970s or 1980s by a French or Italian architect, has a fading allure. Those had been the country’s boom years, when cocoa, its most abundant crop, fetched sky-high prices on commodity markets, and when one aspired to live in Abidjan as one might in the cities of Paris or Rome.

Now, Cocody is the enclave for Ivorian old money. The Riviera neighborhood is also fashionable. Partly as result of the shifting preference for a more suburban lifestyle, not more than seven or eight units in Residences Belles Rives serve as apartments; the rest of the tower has been given over to office suites. On the fifteenth floor, he is alone, in splendid isolation. The owners of the two other flats on the floor seem content to leave them sitting vacant. From his balcony, he has a view of a small, dark-green rectangle on the grounds of the building: a disused swimming pool stained by moss or algae.

Although a swimmer, he is more troubled by the state of the building’s two elevators, which he estimates to be thirty years old, and which continually grind to a halt, requiring repair. Much later, he understands that as the number of owners resident in the building has dwindled, so too have the fees and other funds dried up that went to the building’s upkeep.

_____

A small cohort of security guards in yellow and gray livery watches over the building. They are poorly paid, doubtless untrained. He is proactive in heading off any importuning, sending the men (but, backhandedly, not the woman among their number) as errand runners for bottles of drinking water. In this way he can “dash” them a thousand CFA francs and supplement their incomes in some slight way.

Coming home once or twice at midnight he rouses the guards from their sleep to unlock the double front doors and let him in. And he passes quietly—a little sheepishly—between the thin mattresses set down on the floor of the lobby to enter one of the dreaded elevators. He is self-conscious not about having woken them but about the atmosphere in the lobby, which is airless and fetid with sleep sweat.

_____

Going about on foot, he learns, is not among the benefits of life in a city with a sharp instinct for status; walking, he is invisible to drivers. Also, many city roads lack sidewalks entirely. Drivers typically park along the road shoulders. Commuting by foot entails walking in the roadway itself, navigating not only other pedestrians but also oncoming cars. Still, he persists, leaving home early and going slowly to avoid arriving in the office with the armpits of his shirt darkened by sweat.

A benefit of walking: he is swiftly aware of the immense colonies of bats that make a home in Plateau’s trees, staining the canopy black with their numbers. Large, vaguely crepuscular fruit bats, they leave the roosts when it is still light outdoors and wing their way over the lagoon in search of fruit orchards.

And they are active in bright day; he hears them chittering when he steps out of the office most afternoons to stretch his legs. To satisfy his son’s enthusiasm for bats—they had yet to spot any in Washington, D.C., before he left—he stands at the foot of trees where they have taken up residence and shoots videos on his mobile phone at maximum zoom.

He is more alert to the presence of bats than the locals, among them very many security guards that sit heedlessly in the shade of trees where bats roost. He cannot help but think of Ebola: one accidental encounter—even with guano—would suffice to trigger an outbreak.

_____

The job—in public relations—is demanding, with long hours. Having separated himself from family, he feels vested. In Washington, D.C., he had been a working father and thus had little time on evenings and weekends for himself. He now has rather too much. At first, there is little loneliness: he is in regular contact with his wife and with his parents, whose interest in how he is faring is matched by an interest in the country’s political developments.

Like many members of their generation, his parents consume far too much news, in his view. They are aware—even before he is—that first one, and then a second Ivorian prime minister has died in office during a short space of time, triggering conspiracies about poisoning. Still, it is tame stuff by comparison with the QAnon phenomenon. Perhaps that’s the point. He should be reading Jeune Afrique and The Africa Report but cannot wean himself off The New Yorker. Côte d’Ivoire’s sectarian undercurrents, the turmoil unfolding in Mali and Burkina Faso to the north—putsch and counter-putsch, hotel bombings—are of less interest than the disintegration of the U.S.

But he is caught too between a sense of awe at the energy and urgency of the African continent, its youthfulness on one hand, and skepticism toward the narrative that Africa is rising on the other. For himself, he has worked out a satisfactory stance: he is not in principle opposed to Africa’s rise, is simply wary of the cost at which it will come, and who will bear it. He is far out of step with the zeitgeist, that is unmistakable. His age has something to do with it, of course (of course!). But he is no less out of step with his African peers, who have mostly elected to make a life outside the continent or else knuckled down in Lagos, in Accra, and have done their bit.

Where does this leave him, who is neither an earnest migrant to the industrialized world nor a faithful son of the soil? He, who is grateful to have been born in an ex–British colony but feels more at ease among francophone Africans? Is he too idealistic or too cynical? Overly Romantic, in a Byronic sense?

Lagos, Nairobi, Johannesburg: these cities increasingly are run by mimic men. By financiers and business founders speaking an argot he thinks of, with some resentment but not without cause, as particularly American. Disruption, innovation, start-up, market liberalization. Their glibness about doing right and doing good is proof that Africa’s technocrats have learned to wear that “ingratiating moral mask which a toughly acquisitive society wears before the world it robs,” in the words of Conor Cruise O’Brien. O’Brien had been speaking of liberalism, but the sentiment applies equally to the neoliberals’ fetish for consumer choice.

The ethos of Africa’s elites is a syncretic blend—technocracy and religious faith—that closely echoes North American values rather than European ones. He cannot be sure how sincere are the protestations about serving God; what is not in doubt is that whether Africa rises or no, the pious capitalists will get their payout.

Mimic men. He’s reached for V. S. Naipaul’s epithet with a little glee. The Trinidad-born writer, in his view, had a far more acute eye for the absurdities of both colonizer and colonized than his many African critics, racist though he likely was.

_____

Through his landlord, an old acquaintance, he has a readymade social circle in Abidjan. By and by, the locus of leisure time shifts to Assinie, a coastal resort two hours away that is turning into a weekend Riviera for the country’s elites.

Many of those he meets are one or two degrees removed from his own friends, who are elsewhere: Johannesburg, Maputo, or Washington. He is welcomed readily, offered ample opportunity to be, even if temporarily, part of the circle.

“So will your wife and son join you at some point?” The question is put to him more than once when it comes out that he is in Abidjan sans famille, put to him in faintly presuming tones. “Probably not. I don’t think Abidjan would work for them.” He is not opposed but would prefer that his wife and son visit first, see the place, which is unlikely given pandemic restrictions. He understands the hedging answer does not help, contributes to the impression he is reluctant to reunite with his family, perhaps because he has taken a local girlfriend or hopes to take one. Still, the glances he fields from curious interlocutors are knowing rather than judgmental.

His ambivalence about bringing the family over is opaque even to him. He tells himself it is the blandishing life of the expatriate he finds distasteful: the not entirely avoidable creep of complacence that comes with employing a driver, a housekeeper, a nounou, a gardien. But he is also fearful that Abidjan would make an entitled brat of his son while crimping the independence the boy will—theoretically—gain in Washington.

And there is also the matter of racial politics to consider. Lagos and Accra have an advantage over Abidjan: racial hierarchies are far less apparent in those cities. The Ivorian economy depends heavily on a class of French and Lebanese businesspeople that form a wealthy minority and a considerable proportion of the country’s overclass.

One afternoon, over a lingering lunch on the upstairs verandah of an acquaintance’s house, there is an encounter that reminds him of the anglophone/francophone tension within him. A man—call him Alain—on the periphery of the social circle is talking self-indulgently about music and Paris. The city is, in Alain’s view, incomparable, the greatest city on earth. Without malice, in genuine confusion, he quizzes Alain, why are you here in Abidjan rather than there?

Certain opportunities there are closed to me as a black man, comes the response, which he permits to pass without comment.

_____

Over thirty years earlier, he’d relocated from the UK to Côte d’Ivoire hopeful that quitting Margaret Thatcher’s Britain might offer an escape from racism. The Yorkshire boarding school he attended had been about twenty miles from Leeds, an epicenter of the National Front movement. Disabusal had been swift. On arrival at Abidjan’s airport, he and his sister, B, were detained, owing to the absence of yellow fever stamps in their vaccination cards. A health official told them entry into the country without the vaccination was impossible; it would be necessary to submit to an injection then and there. Surely, they could get vaccinated at a clinic while in-country? The official was unmoved by their concerns about the airport’s hygiene conditions. At last, after perhaps fifteen minutes of listening to objections, the official glanced once more at the Sierra Leone passports in his hand. He said, with little asperity, “On vaccines même les blancs ici.” “We vaccinate whites here. Do you vaccinate whites in your country?”

Their resistance instantly caved. In short order he and B had been jabbed and released into the airport’s arrival hall. With hindsight, he’d understood their protests collapsed because of the official’s naked—and unanswerable—embrace of racial and national hierarchies. He is unsure how he would respond now, in adulthood, in middle age, to such an encounter. With irony? With some answering provocation, secure in his status as an expatriate arriving to take an international job? His French is not good enough for contempt.

_____

Three months after his second arrival in Côte d’Ivoire, the spread of the coronavirus triggers a switch to working from home. Alone in a city without quality healthcare, he is at first wary of the coronavirus. The shift to pandemic mode vindicates his choice, as he sees it, to rent an aerie of a flat, a place to float above the disease spreading unseen in the streets and offices far below.

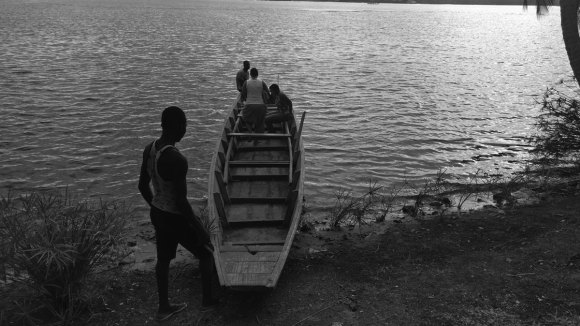

He begins spending more of each day on the balcony, drinking a cocoa/coffee concoction, working, writing, taking meals. He is high enough that the mosquitos—and few flies—trouble him. From here, he has a vista of Abidjan’s Saint Paul’s Cathedral; he interprets its design as symbolic of Christ pulling followers in his wake. Below him is the highway and Cocody lagoon, often fetid with unprocessed sewage but alluring, nonetheless. Solitary men paddle its expanses, naked beneath the blare of sky and sun. Are they fishers? Where are they going? Coming from?

A great deal of infrastructure development is under way in and around the lagoon. A Chinese firm is building a bridge—its construction appears complete, but it has not yet opened—that will cut the commute from Plateau to Cocody and Riviera. A second project under way—on the Plateau shore of the lagoon—seems to move ahead only haltingly: the development of a marina. Some days a barge floats an excavator ten or twenty meters offshore to desultorily dredge silt, perhaps preparatory to backfilling the lagoon for construction of docks, and an arcade of shops and restaurants. If ever completed, it will increase traffic immensely on both sides of the lagoon.

In the weeks of working from home, swifts are his most frequent companions. They live far below in the great eaves of his apartment building. There are moments when they seem to be performing a great social dance, as many as twenty or thirty birds weaving patterns with their movement, and flitting in close to the railing.

He is similarly attentive toward the pied crows—numerous and assertive on the ground and in flight—and their antagonists, the black kites, Milvus migrans, a bird of prey that he has yet to witness actively hunting. Daylong, crows and kites engage in asymmetric aerial conflict, the former mobbing and divebombing the latter, which, outnumbered, do their best to ignore these attacks. Territory for scavenging must be at stake, and perhaps vulnerable nestlings.

And then one day, deep into the rainy season, and probably weeks after the fact, he notices the kites have gone. He no longer hears the high ringing calls which he had unconsciously, anthropomorphizingly, even chauvinistically resisted identifying with a bird of prey, even one that lives by scavenging.

Thus are his days of remote working marked. And then an unexpected encounter in Residences Belles Rives jogs him back into the human sphere, providing fodder for conversations with his parents. The building’s superintendent joins him in the building elevator one morning as he descends. The man, setting to tearing down old flyers taped to the mirrored walls of the elevator car, idly tells him the president is on the premises. The president of the building association, presumably.

But the man he means is the nation’s president, who has come to see a dentist with a practice in the building. Which floor, he asks the super, disbelieving and not only because of the absurdity but also the possibility that the elderly president might get trapped in either of the building’s rickety elevators. The super is not pulling his leg: crowding the lobby are five or six security officers in dark suits, sunglasses, and two-way radios on their hips; the look strikes him as modeled on American or British television shows about secret service personnel.

A pattern has been set. He is returning on foot from a nearby supermarket when he observes people running in groups and singly along the same route he himself is following. He is not alarmed, more curious, even when he draws up to his building to find a crowd of perhaps seventy-five people milling about outside on the sidewalk.

The president is in the building, one of the yellow-uniformed guards confirms, and has let it be known he will hand out largesse to his followers; it is an election year, and the polls will open in a few months. Curious to see how the process will unfold, he waits among the throng. Surely ADO, as the president is known, will not himself press wads of CFA francs into eager hands. Fifteen minutes pass, twenty; perhaps the president is having a root canal. Unhindered, he enters the building lobby and proceeds upstairs to his flat to prepare supper. Half an hour later he glances out of the kitchen window to see that the gathering has dispersed. The money has been distributed, he learns, but can glean no details as to how this has happened.

_____

By July 2020, his sense of vulnerability to Covid-19 has faded. If the coronavirus is carrying off a great many people in Abidjan and Côte d’Ivoire, there is little evidence of it. In Washington it is different: the pandemic is raging and has closed the District’s schools and its indoor and outdoor municipal pools. As a stopgap, his son goes to his grandparents mornings as the child’s mother works. He is unsurprised, even untroubled that the boy passes this time watching a great deal of television. What he dislikes hearing is that his mother is allowing the boy to treat her like a lackey. His wife is too circumspect—and too grateful that someone is minding the child so she can work—to raise the matter with her mother-in-law. The intervening distance, a sense of powerlessness magnifies what might be a small matter. Magnifies it enough to renew the feeling he has abandoned his family.

_____

What is really troubling him is the realization that his mother, a once-domineering woman—a prototype tiger mother—might be too elderly to take her youngest grandchild—perhaps the most willful of the four—in hand as she has with the others. The conversation he has with his mother is a difficult one, requiring that he not shame her nor imply she is past it. Don’t give in to the demands, he tells her, and afterward, wonders if he has overreacted. It is after all the role of grandparents to be indulgent.

A very difficult summer overall in Washington, with the indoor and outdoor pools closed and playdates foreclosed.

While his son is wading in the creeks for which Rock Creek Park is named, he has returned to spending weekends at Assinie in the company of a familiar crowd, for whom the pandemic has faded away, if it ever existed. As they hug and buss one another’s cheeks in the French style, it seems churlish to turn away from an embrace, to offer his elbow for a bump. Once—the first time—he does it and then consents to the more intimate greeting. They would of course humor him just because he is an American in their eyes, and thus entitled to be a little uptight, but he refuses to play to tropes that do not apply.

The weekend house is open to the elements, is windswept and so, a little glibly, he lulls himself eating and drinking around a long communal table with the thought that he is not really indoors. And then for days afterward he is flushed with guilt and fear, scouring for proofs he has contracted the disease. His behavior is a form of escapism, guilt-edged—a response to feelings about what is taking place in Washington.

And then in September, after months of stasis, of reaction to the pandemic, a shift, for himself and for his family. His wife and son have left the U.S. for Stuttgart—his mother-in-law lives nearby—and his wife has left her job to go into business with a few colleagues.

Rather than buying a car, as he has begun vaguely to consider, he must tighten his belt in Abidjan. And so impetuously, he leaves Plateau, and Residences Belles Rives for another apartment in a section of Deux Plateau, a move that cuts his rent almost by half. His new place is in a suburban quarter ten minutes’ walk from Rue des Jardins, a thoroughfare with restaurants and a supermarket. He misses the soaring views, and sidewalks are no more common in these parts than in the CBD.

And then he is in Germany, reuniting with his wife and son nearly a year since he last saw them, and a near stranger to the child. Stuttgart, which he knows quite well, is a middle ground between Washington and Babi, free of the insanities of both. An overdue visit, and one that breaks the spell of Babi in a way that a return to Washington would not have, could never have. And in a way he only understands after he returns to Abidjan, to an unfamiliar and bare flat flecked with the varicolored shit of geckos. It is as if he can no longer see Babi, although what preoccupies him is a sort of fantasy family life, in which the three of them enjoy the best bits of Abidjan and the best bits of Stuttgart (he hates the unrelieved Baden-Württemberg winters).

He has begun, again, to think about relocation.

_____

Photos by Olufemi Terry.