By now the divide is clear: it looks like the same divide that bedevils prose fiction, or did until recently. Comics and graphic novels get framed as serious literature, if they’re accomplished enough, but only if they seem to portray Real Life. They might become bestsellers, as well as prize winners: consider Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, or Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. Comics with fantasy, science fiction, or other anti-realist frames might sell like hotcakes too (consider Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples’s Saga), and they might inspire other creators, but they’re not taken so seriously by critics, nor by the academy, and they’re not often granted the same kind of scrutiny (except by the people who want to make them). Comics for younger kids bypass all this gatekeeping, and they reach sales numbers undreamt of by Alison Bechdel’s fans—and undreamt of by Batman’s. But in the adult world the division remains.

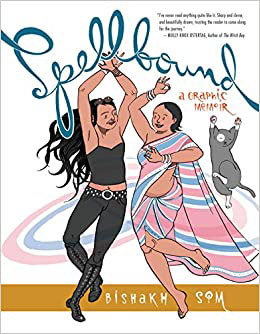

It’s time for that division to go away: this pair of impressive book-length comics shows why. Bishakh Som is a New York–based creator who worked as an architect before she quit the field to draw full time; she’s also a trans woman who came out as an adult, a self-described “desi-futurist,” and a child of Indian immigrants, raised in the U.S. All those identities flow through Som’s two new collections, Spellbound: A Graphic Memoir and Apsara Engine, the first largely realist, the second partly fantastical. The difference shows not only why critics of realist comics need to be open to fantasy, but also—and more important—why trans artists, trans bodies, and trans lives often demand space outside what we call the real world.

Spellbound collects the full-color, quasi-autobiographical, one-to-four-page comics Som drew in the years when she was leaving architecture, trying to find herself romantically and professionally, trying to send more comics out into the world. Almost all the strips in Spellbound follow not a skinny trans cartoonist named Bishakh, but a curvy cisgender woman named Anjali who shares Som’s background, locale, and professional trajectory: Som drew the life she would be living if she were cis.

The slices of life, the self-deprecating humor, the slow-moving realism that are the default modes in Spellbound are at once lovely, and literary, and consistent, and somewhat low-stakes, somewhere between the realist angst of Adrian Tomine and the charm of Lucy Knisley (who has, like Som, drawn for the New Yorker). Anjali goes on bad dates and better ones, tries to sell comics to publishers, finds herself sucked back into architectural gigs (with a focus on fancy bathrooms), drinks too much (and not enough), and self-narrates, and self-narrates.

A typical page from Spellbound displays Anjali’s misadventures in four or six equal-sized panels, each overlaid by a text box with her thoughts, with neat serifed mixed-case lettering like Hergé ’s from Tintin. Sometimes Anjali makes fragile plans with friends; sometimes she just wants to stay at home with her cat, the limitlessly charming Ampersand, distinguished by a white circle around one eye. (Late in the volume, Anjali struggles to get out of bed and pursue her comics career, while Ampersand stands on top of her, pelting her with counterproductive zzzzs.) Sleek parallel lines, with furniture fit for space-challenged New Yorkers, accompany panels of Anjali alone under blankets, or at her desk, or just lounging in her apartment: these images sometimes crash through the emotional floor into the territory of Chris Ware, as the point-of-view character, with her round face and small eyes, fails to stay brave amid tedium.

It’s easier for these panels to embody sadness, or boredom, than to show how Anjali finds strength. What ought to be the happiest segments (“I can’t believe it—eight straight hours of drawing”) run into the problem faced by all Künstlerromanen (stories about how someone becomes an artist): artists and writers, depicted at work, give you almost nothing to watch when they’re actually getting their chosen jobs done. Partly as a result, this series of short views ends up focusing on Anjali’s increasing dissatisfaction. What can she do, what should she do, to make a living, to stay insured, to construct a social life and an erotic life for herself, now that she’s cleared out so much time to draw?

Before she can tell us, Som shows us how Anjali got to this point. Anjali (and perhaps Som) grew up first in Addis Ababa and then in Manhattan, the child of diplomats, a shy kid with an international friend group; a teen friend taught her the basics of comics, rapidograph, and Zip-a-tone. When very young, Anjali drew “maps of fictional cities and floor plans of imaginary hotels”: as an adult, she writes on an androgynous lover’s naked back, in bed, “I WISH YOU WERE REAL.”

This shift from image to word, as Anjali grows up, helps neither Anjali’s mood nor Som’s pacing. Childhood scenes delight, where present-tense urban-single-life follies can drag: “Still too much dialogue maybe,” Anjali says about one work in progress, “but whatever . . . people need to read more.” But they don’t: they need to read exactly as much text as a particular comic requires, and these comics sometimes use more than they need. At their best they seem to be straining against exactly the kind of diary-chronicle that Som says she initially set out to make.

Then Anjali leaves New York: first to negotiate her parents’ declining health (she helps them move back to India), and then to the Adirondacks, where a lovely getaway with another Desi lesbian friend turns into a night of confusion and heartbreak. Six panels (rather than the usual four) on a page of hiking through dense woods introduce a double-wide panel where Anjali and her friend discover a lake, clean air, the open sky. When this friend advises her to “Live outside your head for a spell” we are bound to agree.

Anjali’s second, and more satisfying, romance plot pairs her with a darker-skinned trans character, Titania: the two of them come together in the title strip, which might depict a sex dream. It also describes a kind of openness to other people, other lives, and (not by coincidence) other color schemes and panel constructions. “I usually have such intense daily contempt for other people,” Anjali admits, that “it’s jarring” to fall so hard for someone. But it’s in the falling, in the taking of risks, in the opening up of boundaries—between panels, between people—that Anjali, and hence Som, seems most alive. “There are moments when I am unencumbered by my body,” Som-as-Anjali muses when with Titania, “like weights that have dropped, ballast that has been jettisoned. This is witchery of the sweetest kind.” Further hangouts with Titania do not open the page up but slice it further down, at one point into eleven talking-head panels on the same page: shockingly, this page also works well, perhaps because it, too, departs from Som’s visual norm.

Spellbound ends by slicing through another boundary, the one between Som’s fictionalized environment and the real world. Anjali meets her creator, Bishakh Som, on-panel (Som draws herself). “Thanks for slogging through all that. Sorry about all the self-pity,” Som tells her readers, before explaining that “Anjali began as a substitute but she’s become her own—” at which point Anjali interrupts. Som also tells the world that Titania reflects Som’s own experience meeting a charismatic trans woman, who in turn helped her to come out. “I also met a trans girl at a party,” Som explains (drawing herself in her actual body, thinner than Anjali and in gray indie-rock clothes); that girl “opened up to me the possibility that I was like her.”

In a classic transfeminine moment, Som needed to see who she could be through others’ eyes before she could learn to see herself. The very self-conscious, sometimes hesitant Anjali/Som does a good job showing how hard it is to imagine a future that nobody else can yet share: how hard it is to change the narrative other people carry about you, even if you think you can change that narrative for yourself. There’s no substitute for making a friend (or finding a lover) who sees you as you should be seen. But books and comics can anticipate, or model, that friendship. And Desi professionals, Brooklyn-based singles, slow-to-emerge trans people, former Goths, autobiographical comics creators, “newly hatched full-time artists” (to quote Som), may well see themselves, or ourselves, or watch ourselves seeing ourselves, in the trio of Titania, Som, and Anjali.

And then we may want to see more. The Som who drew Spellbound works to participate in a line of semi-auto-bio queer comics that goes back at least to the 1980s (Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For) and early 1990s (Leanne Franson’s still-too-little-loved Liliane: Adventures of a Bi-Dyke). She works, too, to place herself in a line of literary realist comics creators (such as Satrapi, and much of Ware). And yet Spellbound soars whenever it rises past realist constraints, and past the regular grids and Ware-ish details that come with them: in the sex scenes, in the forest, in parts of Anjali’s/Som’s childhood, where big text blocks take a holiday and Som gives us more, imagines more, to see.

Realism—to put it quickly—is not enough: not enough to capture how the heart and the mind work when they are at their most active; not enough, or not right, for this particular comics creator’s cast of mind. “I wonder if there is even a market,” Som-as-Anjali muses midway through Spellbound, “for the kind of comics I’m doing . . . no superheroes, robots, zombies, vampires.” I wonder instead if the kind of comics she’s drawing are the kind she most wants to read. The Som who draws those fantastically swirly sex scenes, who seems happiest when the captions drop away, who wonders whether New York City is worth it, seems to want more than the visible world, with its custom bathrooms and its crowded cityscapes, can give. And the glory of her uneven but exciting collection Aspara Engine accumulates where and whenever her pencil can give her what she seems to want.

It’s exciting not least for its variety: nine tales, most about couples coming apart or together, arranged—to put it crudely—from least to most trans. “Come Back to Me” begins slowly, smoothly, in black and white with captions and illustrations and an old New Yorker feel, the story of a straight couple’s engagement by the sea. Then merfolk arrive, and with them, pastel colors. When and why and under what circumstances would you agree to a dalliance under the sea? What would you do if you encountered a preschooler who was also, in a low-key way, a dog? That’s the donnée in “Threat,” which ends up both pleasant and slightly Kafkaesque: it’s the kind of story that works much better as a comic than it could as prose or film or verse.

And that’s true for most of the rest of the stories Apsara Engine contains. The title story revels in its impossibly detailed futuristic background, an intricate Escher-ish maze of vents and pipes and HVAC, a jade and ruby and cerulean megalopolis. It’s fun to read in a way that implies (though who knows?) that it must have been fun to draw, though it’s hard to know how much fun the lightly sketched characters—each in their own apartment, or by their own pool—will have in the coming disaster or revolution. “It is the right duty of every student to refuse to participate in the same state-sponsored social enterprise that—” reads one character’s thought balloon (strikethroughs in original) . . . and the story ends there.

Apsara Engine, the more ambitious graphic novella, becomes even more fun to see, though it takes longer to get there. In “Swandive,” Onima Mukherjee, a trans woman and a scholar of “trans cartographies,” gives an academic talk (we see her elaborate cartographies in the comic). After the talk she meets Amrit, a nonbinary (no pronouns at all preferred) graduate student at “Amherst” (presumably UMass Amherst). Amrit is “stoked to see another Desi trans person,” and they discuss, over drinks, the “perpetual minefield” of overlapping identities. Then they kiss, and it’s awkward, and we think they might hook up—after all, she takes Amrit back to her hotel room.

Instead, Onima draws a vial of her own blood and uses the blood to start painting a map: the trans cartographies she imagined, made real on a big flat screen on the hotel room wall. It’s exactly the self-conscious figure for art, for comics art, for what trans art can be, that Anjali and Som seek and never quite find over the course of Spellbound. And—as Som draws the cloverleaves and paths and garden-diagrams and high-tech interiors that constitute their imagined city—it’s the refuge and utopia and future that stressed-out trans people today may want, the sort of science-fictional place that lets us imagine how to improve the real one. Imagined places, after all, exist in our heads, doubly so when we write and draw and share them.

Som’s architectural background finds magnificent use in the cityscapes, bicycle paths, and engineered chambers where the characters in Amrit’s and Onima’s maps discover themselves. Onima draws, and describes, “an allée of bodhi trees, patches of neem, tulsi” and “an island with record stores and a penny arcade, where they sell the best ice cream.” Amrit adds “free housing for trans and gender-nonconforming kids” with “their own health clinic, a recording studio, and a bowling alley.” There’s also “a small hotel, a library, a museum of weather” and “an old abandoned steel factory that’s been taken over by a clowder of feral cats.” Who wouldn’t want to go there?

The right analogy for these creations might not be Ware, with his sad exactitudes, but Shaun Tan, the Australian artist who drew the wordless book-length comic The Arrival, another gray-scale consolation about a finally uplifting imagined land. Som has not reached Tan’s level of craft (who has?) but she has figured out how to draw imagined spaces that comment, insistently and sometimes delightfully, on the built environments we can already find. She can think about how to improve them, too: how to see a future that is neither the present nor the past (nor the white future of so many white artists, even trans artists, even today). “It’s a future, I suppose . . . one of many,” says Onima. Now we get to make it come true.

Toward the close of their tale, Onima and Amrit seem to enter their own creation, almost losing their physical forms amid clusters of acute angles and sleek curves, having another meet-cute at “moon month” in the future, and coming to rest by a sign reading “It’s OK.” And for them, it is. A swan dive is normally, colloquially, something like a face plant, but here it means, instead, a deep dive, an investigation into what’s under the surface, what else imagination can swim far enough to find.

That imagination does not swim so much as fly in “Love Song,” whose nostalgic human protagonist sits on a park bench feeding fantastical creatures, first a four-footed, attractively catlike pigeon and then a friendly variation on the mythic harpy—woman’s head, raptor’s wings, and feline body. As in all Som’s best work, we begin with realism and end up in the air: brought aloft by a semi-divine bird, like Chaucer in The House of Fame, our heroine contemplates “childhoods that were cut in half,” “Sarah Jane who played guitar in my band,” “Nazia, who I loved so much,” shown as a four-armed composite, like a Hindu deity. “Auntie Sarita in a shimmering kurta,” “dear Lavinia, you impetuous pup,” “Selina . . . we should have been better friends at school, I know”: this love belongs not to one partner but to all the people—in this case, all the women and girls—now gone from this life, and seen in visions, up in the air.

Even the volume closer, the otherwise realist “I Can See It in You,” gestures toward the realm of the fantastic in its plotline. In it Som’s alter ego Anjali, drawn in lovely grayscale rather than the full color of Spellbound, visits a party to see her ex, Rajiv, and his new girlfriend. Anjali seems drawn far more to her than to him. Anjali also seems able to see the future, telling him that the relationship won’t last (this new girlfriend will leave him “for a white guy”); after a kitchen flirtation and panel after panel of post-breakup angst, the vignette dissolves into wordless pages as a dejected Rajiv leaves the crowded premises.

Why would a figure as talented—as versatile, as inventive—as Som end this volume this way? Why would a comics creator so good at imaginary backgrounds, never-built architecture, dream maps, mythic creatures, and fantasies partly fulfilled begin and end in realism? Som makes no case for superheroes here, no case for action-oriented fantasy; to judge by the slow-moving, pensive figures here, she has no interest in the kinds of dynamic art styles those genres would require (if there is a modern painter whose people Som’s people resemble, that painter is certainly Fernand Léger). It may be that we do not yet have a stable name, much less a stable audience, for the kinds of comics Som seems best suited to make: comics whose prose equivalents would be called slipstream, or weird fiction, or magic realism.

We may not have a name, but we have the comics, and they do need to be comics: work that proceeds according to the pace of the viewer’s eye, not the pace of the film editor; work that allows us to scrutinize the pigeon who turns into a sphinx or a girl, or to accept it as part of the story. This kind of imaginative exploration, where we can dial up and then dial down the sense of wonder, the distance from real life, seems peculiarly suited, as well, to lives that were fantasies before they were lived; to the lives of anyone hemmed in, for a while, by parents’ expectations, by stringent economic requirements, or (especially) by a body that does not feel like the body we’re supposed to have.

There is a sense in which all trans lives are fantasy first; a sense in which all trans stories are stories about metamorphoses, imaginary bodies, and unbuilt cities. That sense nibbles at the realist edges of Spellbound. And it comes across in Apsara Engine, especially but not only in “Swandive.” Of course some of the stories (“Swandive” among them) incorporate other tropes that only South Asian and South Asian diasporic readers might wholly recognize. These are not, by and large, stories about white people: I, a white trans lady, am certainly missing important dimensions of these Desi characters’ lives. They are, however, stories about trans and queer people, who—whatever our origins, whatever our other identities—require shifting bodies and extra worlds: undersea, in the air, in the future, where cities and gardens interact and intertwine, where we might sketch our next home.

They are, too, ways to see the queer utopias forever receding before us, the consciously temporary near-future happiness, envisioned by the late José Muñoz, and by other thinkers who looked at the straight-centric world and imagined a better place: to quote Muñoz, “the future is queerness’s domain.” In ways that should be obvious by now, queer people, trans people, need lives that look and feel unlike the lives we grew up knowing: we need lives whose geographies, whose economies, permit us to become ourselves. The Som of Apsara Engine begins to envision them.

The contrast between these two books by the same creator looks not only like the contrast between realism and whatever lies beyond it, not only like the contrast between actually existing cities organized by patriarchy and future cities that might run differently, but also like the contrast drawn in Rita Felski’s magisterial recent studies of how literary critics read. In The Uses of Literature and the books that came before and after it, Felski suggests that modern critics have learned to read primarily for critique, for accurate representation and disillusion, whereas readers (including comics readers) who are reading for pleasure, in our free time, seek a handful of other desiderata. We want to see ourselves, to find allies, to feel recognized. But that’s not all. We seek not only “recognition,” “knowledge,” and “shock” (to use Felski’s terms) but also “enchantment”: a space new and different, mysterious and pleasurable, one we can visit, one where we might wish to stay, even though “we know ourselves to be immersed in an imaginary spectacle.” In Proust’s account, Vinteuil’s sonata generates that effect on Marcel, and perhaps on Proust’s readers; Thor: Ragnarok, viewed in the right mood, can generate that effect too.

Highbrow critics and the canons we make—the canons of “literary” fiction and poetry, of film and music and comics, of prize-giving and syllabus creation—almost always account for recognition, and for knowledge. Sometimes they account for shock, when literary works reframe unpleasant truths. Comics, like any other form and medium, can implement all three virtues. Joe Sacco’s reportage in comics form from Palestine and other modern war zones can shock First World readers with every page. The terrific academic critic Hillary Chute has penned an entire volume, Disaster Drawn, about how comics’ hand-drawn images convey historical atrocities. Both Art Spiegelman’s MAUS and Bechdel’s Fun Home (which also consider comics as maps!) respond to public and private catastrophe.

Spellbound and Apsara Engine do no such thing. Their pains—and they hold many pains—are small, even petty, compared to the way Apsara Engine constructs imaginative pleasures: these books are strongest when most enchanting, most able to swoop and leap and draw new maps and get far off the ground. Short uncollected works visible at Som’s website show her achieving new altitudes in other ways. “Little Nemo Vs. Anjali and Ampersand” (drawn for an anthology in tribute to Winsor McCay) places Som’s alter ego and her ultra-charming gray cat in an unstable interior, full of staircases that lead nowhere and dream-logic that guides impossible architecture. A series of watercolors called Plague Diaries, completed in 2020, pairs Anjali with another Desi figure, in a mix of swimwear, traditional South Asian attire, and punk garb, dancing through clouds and ribbons and gargantuan flowers. Similar figures in earlier paintings cavort and leap through prismatic arrays of girders, through crystalline shards in vacant space, or perched on balconies in a stylized, curve-heavy city that resembles Prague. These figures, like Onima and Amrit, inhabit an incipient queer utopia: I want Som to draw—because I want to see—what they see.

_____

*an essay-review of Bishakh Som’s Apsara Engine (New York: The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2020. 250 pp. $24.95) and Spellbound: A Graphic Memoir (Brooklyn, NY: Street Noise Books, 2020. 160 pp. $18.99).